VIOLENCE IN REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

International and European law recognises sexual and reproductive rights as human rights, which is why their violation is also a violation of human rights. In Slovenia, reproductive rights are protected by a constitutional provision in Article 55 that guarantees the right to the freedom of choice in childbearing and imposes on the state the responsibility for creating conditions enabling the exercise of this right. Nonetheless, in practice, its exercise is often limited, which can lead to different forms of structural and institutional violence. Informal practices in diverse institutions responsible for safeguarding reproductive health often include discriminatory treatment. This undermines the right to a safe and satisfying sexual life and informed decision-making regarding one’s own body without fear, discrimination or violence.

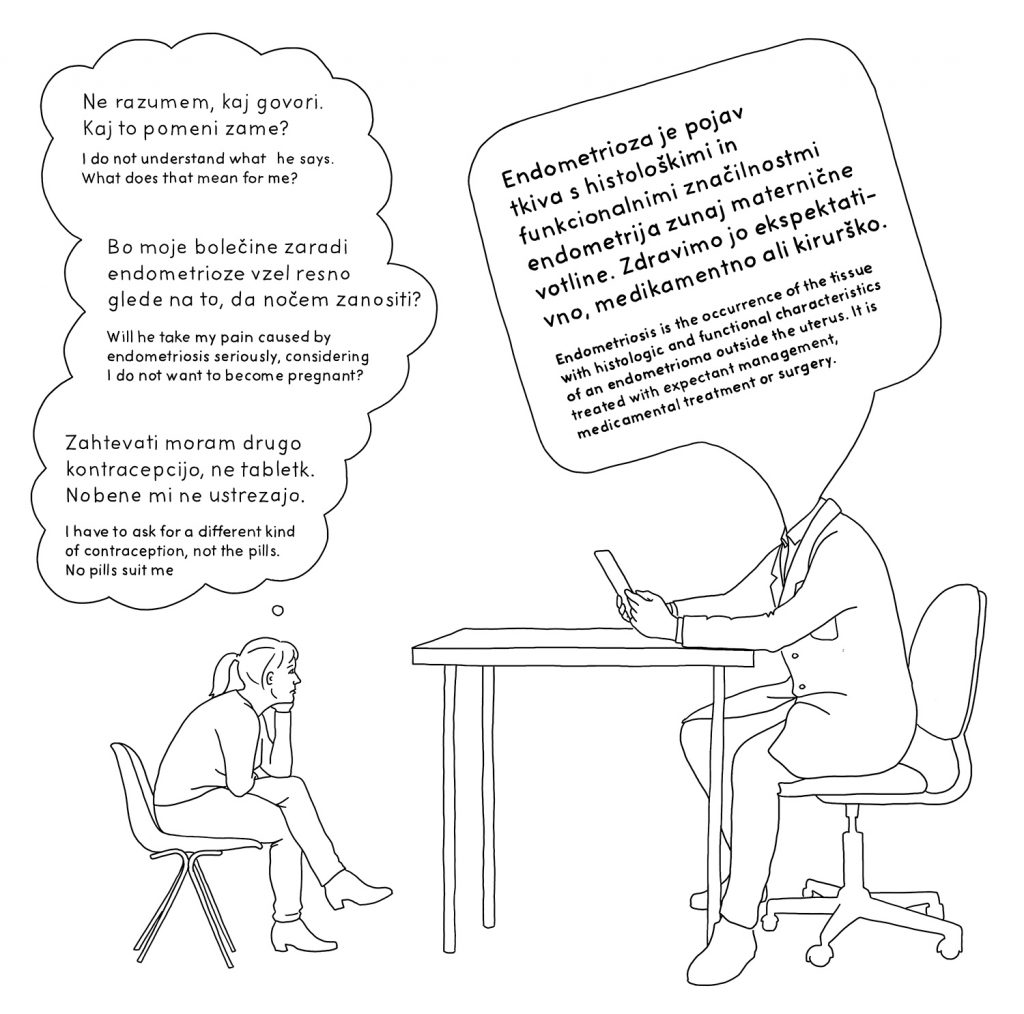

Women’s experiences reveal a gap in preventive care. Often the first gynaecological check-ups only focus on the prescription of contraceptives and neglect a broader aspect of women’s reproductive health. Diagnoses often lack sufficient explanation and information. Even though abortion is legal, obstacles occur in the access to this service that are related to deterrence from abortion or medical personnel refusing to perform this service due to personal moral beliefs based on which they exercise conscientious objection. Women’s diseases, such as vaginismus, endometriosis, and polycystic ovaries syndrome, are underestimated, which results in delayed diagnosis. Women report being denied check-ups and referrals to medical specialists, and refusals by medical personnel to treat them due to gender norms (such as the refusal to treat endometriosis, if the woman does not express the wish for reproduction). Moreover, the lack of gynaecological counselling clinics for young people and specialists in gynaecology presents a structural problem due to which many women are not ensured timely first and regular access to check-ups, contraceptives and medical care.

Following the example of the Croatian campaign #PrekinimoŠutnju [BreaktheSilence] from 2018, in the framework of which over 400 women gave their testimonies about discrimination and violence on the part of gynaecologists during giving birth, also women in Slovenia shared their experiences of violence related to giving birth within the homonymous campaign #PrekinimoTišino [BreaktheSilence]. Obstetric violence includes all inappropriate, inadequate and violent aspects of medical personnel’s attitudes toward women before, between and after they are giving birth, as well as inappropriate, inadequate and violent procedures and interventions when they are giving birth. What is worrying is the hierarchical attitude of medical personnel towards patients that does not provide support for women’s autonomy, including ignoring their birth plans, coercion to unnecessary medical interventions and insufficient information about the interventions.

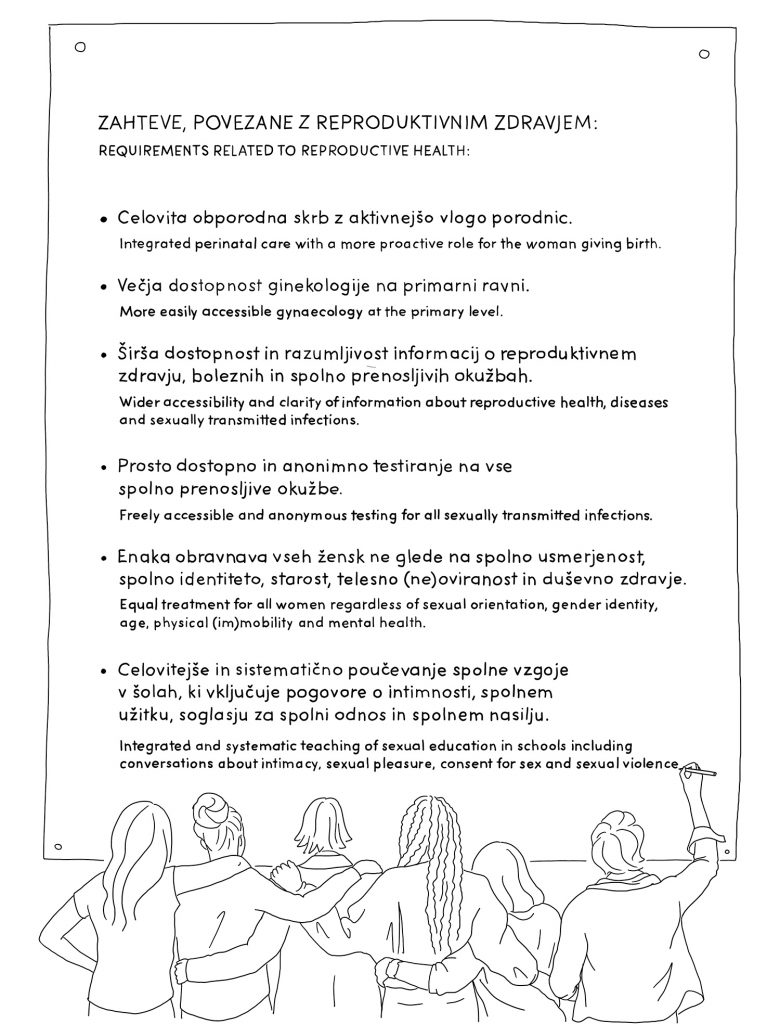

Women’s experiences show that it is necessary for the discussions on reproductive rights to reach beyond the mere legislative framework and also focus on how to ensure easily accessible and high-quality services in reproductive health. In this respect, it is of key importance to encourage open communication between medical personnel and the patients, include knowledge of human and social sciences in medical education, and provide equal, comprehensive, individualised, compassionate and respectful care while giving the patients a more active role. Women should receive appropriate care in such a way that it maintains their dignity, privacy and confidentiality and enables their conscientious choices supported by clear and accessible information on reproductive health. At the systemic level, it is necessary to ensure accessibility of gynaecology and freely accessible anonymous testing for sexually transmitted infections and to introduce a more comprehensive and systematically taught sexual education in schools that would include conversations about love, partner relationships, intimacy, eroticism, pleasure, sexual identity, sexual orientation, sexualisation, sexual violence and consent regarding sex.

Leja Markelj

Text: Fierce Project Group, posvet “Nasilje in reproduktivne pravice” [“Consultation on Violence and Reproductive Rights”], December 19, 2023, Faculty of Arts, Ljubljana.

Text: Fierce Project Group, posvet “Nasilje in reproduktivne pravice” [“Consultation on Violence and Reproductive Rights”], December 19, 2023, Faculty of Arts, Ljubljana.

Text: Fierce Project Group, posvet “Nasilje in reproduktivne pravice” [“Consultation on Violence and Reproductive Rights”], December 19, 2023, Faculty of Arts, Ljubljana.

SOURCES:

- Poročilo o stanju spolnega in reproduktivnega zdravja in pravic v EU v povezavi z zdravjem žensk [Report on the Situation of Sexual and Reproductive health and Rights in the EU in the Frame of Women’s Health], European Parliament, Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, May 21, 2021. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2021-0169_SL.html.

- Fierce Project Group, posvet »Nasilje in reproduktivne pravice« [Consultation on Violence and Reproductive Rights], December 19, 2023, Faculty of Arts, Ljubljana.

- Sabrina Zavšek, »Slovenke z zgodbami opozarjajo na težke porodne izkušnje« [Slovenian Women Call Attention to Difficult Childbirth Experiences], Siol.net, October 19, 2018. https://siol.net/novice/slovenija/slovenke-z-zgodbami-opozarjajo-na-tezke-porodne-izkusnje-foto-480847.

RECOMMENDED SOURCES:

- Ada Černoša, Nina Demšar, Zara Gradecki, Vanja Hreščak and Tjaša Perger Majeršič, Moja roka, tvoja roka: spolno zdravje in spolne prakse lezbijk, biseksualk, transspolnih in interspolnih oseb v Sloveniji [My Hand, Your Hand: Sexual Health and Sexual Practices of Lesbians, Bisexual Women, Transsexual and Intersexual Persons in Slovenia] (Ljubljana: Kvartir Association, 2021). https://kvartir.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/moja-roka-tvoja-roka-drustvo-kvartir.pdf.

- Web page Pravice porodnice [The Rights of Women in Childbirth]: https://praviceporodnice.org/.

- Web page Vislava Globevnik Velikonja, Nasilje nad ženskami in reproduktivno obdobje, v Petra Jelenko Roth (ur.), Duševno zdravje v obporodnem obdobju [Violence against Women and Reproductive Period in Petra Jelenko Roth (ed.), Mental Health during Perinatal Period] (Ljubljana: National Institute of Public Health, 2018).

- Zalka Drglin in Irena Šimnovec, Ničelna toleranca do nasilja med porodom: Za sočutno ter ženski in otroku naklonjeno strokovno utemeljeno obporodno skrb (preliminarna ocena stanja) [Zero Tollerance of Violence during Childbirth: For a Compassionate, Woman- and Child-Friendly Professionally Grounded Maternity Care (preliminary assessment of the situation] (Ljubljana: Združenje Naravni začetki [Natural Beginings Association], 2022). https://praviceporodnice.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/STUDIJA-Nicelna-toleranca.pdf.